Reflection on Frantz Fanon Black Skin, White Masks, Chapter 1

The Language of the Colonizer, or the Sports Entertainment of the Colonizer?

These are some observations made while reading Chapter One of Frantz Fanon’s crtiically acclaimed reflection on the effects of colonialism, Black Skin, White Masks.A version of this reflection was submitted as an assignment for Phil 673: Philosophy of Education, taught by former Kitchenr Centre NDP MPP, Laura Mae Lindo. It has been a joy to take one of her classes, and to get to see yet again, why she was the perfect MPP for Kitchener Centre. Wile I’m grateful that she is a part of the University of Waterloo’ Philosophy department, her hard work and incredible thought process was a huge asset to the NDP caucus, and o Queen’s Park,. and I am sure that I am not the only former constituent who would agree that we miss her dearly in that role

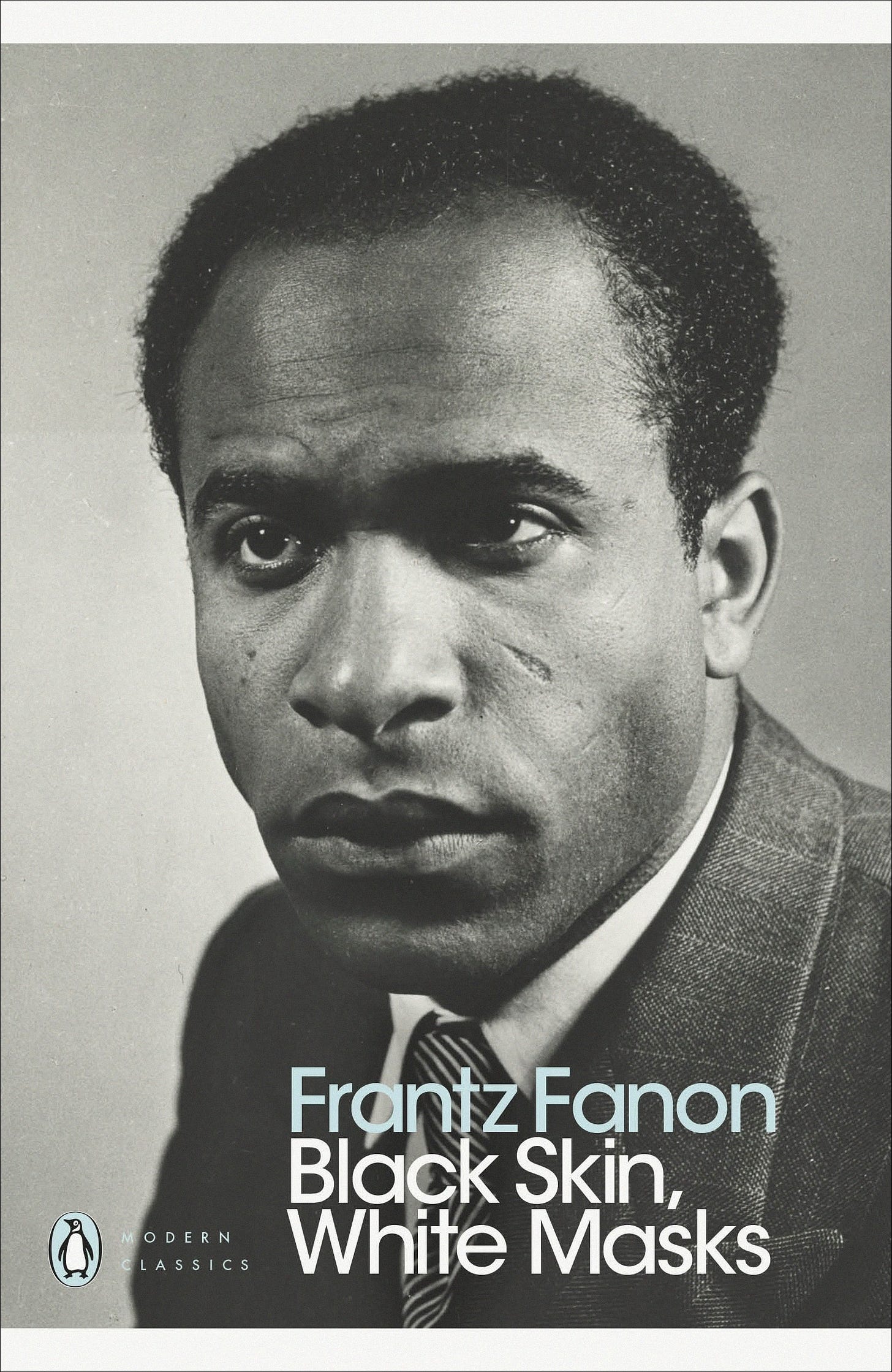

This reflection concerns Frantz Fanon’s book, Black Skin White Masks, particularly Chapter One , The Black Man and Language.

By way of introduction, One of the primary reference sources for professional philosophers in the 21st century is the Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy, containing introductory reference material on any philosophical problem that you can think of. The Stanford Encyclopaedia is written and edited by professional philosophers, ith consensus experts being asked to write the reference material, making the Stanford Encyclopaedia a starting point for anyone doing any kind of philosophical research. All tht to say that the Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy has this to say about the beginning of Black Skin White Masks (←- free full text pdf):

The introduction to Black Skin, White Masks contains key conclusions and foundational pieces of analysis summed up Fanon’s simple declaration: that Black people are locked in blackness and white people are locked in whiteness. As well, Fanon offers a sketch of the relationship between ontology and sociological structures, asserting that the latter generate the former, which, in turn, lock subjectivities into their racial categories. The chapters that follow are in many ways a long, sustained argument for these assertions, venturing into questions of language, sexuality, embodiment, and dialectics. Perhaps most importantly, Fanon’s opening gambit introduces the central concept of the zone of non-being. The zone of non-being is the “hell”, as Fanon puts it, of blackness honestly confronted with its condition in an anti-Black world. The anti-Black world, the only world we know, hides this non-being to the extent that it ascribes a place and role to abject blackness. But the truth is the zone of non-being. In an interesting and crucial twist, Fanon, in the Introduction, does not describe descent into this zone as nihilism or despair. Rather, he counters with a vision of subjectivity as “a yes that vibrates to cosmic harmonies” (1952 [2008: 2]). Descent into the zone of non-being produces this yes and its revolutionary power, revolutionary precisely because the anti-Black world cannot contain or sustain the affirmation of Black life as life, as being, as having a claim on the world. This claim and this yes is the positivity of what becomes political violence in Fanon’s later work.

Across the core chapters of Black Skin, White Masks, Fanon draws together the existential experience of racialized subjectivity and the calculative logic of colonial rule. For Fanon, and this is critically important, colonialism is a total project. It is a project that does not leave any part of the human person and its reality untouched. This is no more evident than in the opening chapter to Black Skin, White Masks on language. Fanon’s reflections on language, racism, and colonialism begin with a wide claim: to speak a language is to participate in a world, to adopt a civilization. The claim reflects in many ways the philosophical milieu of mid-century French and German philosophy, which in phenomenology, existentialism, and hermeneutics explore the very same claim—that language, subjectivity, and reality are entangled as a matter of essence, not confusion or indistinction. But the colonial situation makes this all the more complicated. If speaking a language means participating in a world and adopting a civilization, then the language of the colonized, a language imposed by centuries of colonial domination and dedicated to the elimination or abjection of other expressive forms, speaks the world of the colonizer. To speak as the colonized is therefore to participate in one’s own oppression and to reflect the very structures of your alienation in everything from vocabulary to syntax to intonation. It is true that many Afro-Caribbeans speak pidgin and creole as part of everyday life. But Fanon, in a claim that does not age well in Caribbean theory, measures pidgin and creole expression against French, arguing that Afro-Caribbean speaking, in those registers, is a fallen, impoverished version of the metropolitan language and thus participates in inferiority. In this way, vernacular speech speaks the colonizer’s world into existence in naming the colonized as derivative, less than, and fundamentally abject.

I sat down to read this assigned reading on a Thursday. While that is not so unconventional, Thursdays are the beginning of the week for the National Football League, and I was wanting to get my reading done before sitting down to watch the four 49ers play the Rams.

As I started watching the game I started making a connection between football and the Fanon reading, particularly Chapter One in which Fanon talks about the colonizing effect of forced Language assimilation of Black people from the island of Martinique. The island, a long time French overseas colony, required mandatory instruction of the French language in Martinique classrooms, prohibiting the use of the pigeon Creole that was spoken by most black people on the island, a leftover colonizing artifact from the days of a slave trade sanctioned and encouraged by the French Monarchy across the ocean in Europe. Fanon begins by describing what happens when the Black man leaves Martinique (Fanon’s birthplace) to go visit France, the supposed land of culture, certainly the land of their childhood education, filled as it is with Rousseau, Montesquieu and Voltaire, uncontested giants of French Intellectualism. Upon arriving in Paris, Fanon claims that the Black Martinican, having been taught the language and culture of the colonizer, becomes enchanted with all the glitz and glamour of the continent, coming back to Martinique feels like going back to hell. While he gushes to his friends about the joy of seeing Paris, he recounts seeing cathedrals and churches, which F anon notes h is likely not to have actually entered. Fanon writes, ““the more the black Antillean assimilates the French language, the whiter he gets—i.e., the closer he comes to becoming a true human being. We are fully aware that this is one of man’s attitudes faced with Being. A man who possesses a language possesses as an indirect consequence the world expressed and implied by this language. You can see what we are driving at: there is an extraordinary power in the possession of a language. The more the black Antillean assimilates the French language, the whiter he gets—i.e., the closer he comes to becoming a true human being. We are fully aware that this is one of man’s attitudes faced with Being. A man who possesses a language possesses as an indirect consequence the world expressed and implied by this language. You can see what we are driving at: there is an extraordinary power in the possession of a language.”

What does Fanon’s argument about the Martinican’s language assimilation have to do with football? It turns out that in both the National Football League and the National Basketball Association, both the top professional leagues for their sport, between 70 and 80% of all players are Black. That is, both professional leagues depend on the labour of Black men to put on an entertainment product largely consumed by and paid for by wealthy white men. Interestingly, the only way to the big leagues in both basketball and football is through a minor league system that relies on higher education to contribute to player development and help to separate the good players from the great players. While it sounds good on the face of it that prospective athletes, especially Black athletes will be able to leave the development system with a university education, the challenge comes on the field on Saturday. Until recently, the national body that oversees collegiate sports in the United States, the NCAA, has forbidden athletic programs from providing players with any kind of compensation for their physical labour on the field or the court. The NCAA has handed out millions in fines over the last 80 years to schools that allowed a player to to accept things like a free car in exchange for a sponsorship with a local car dealership. The NCAA considered the use of a vehicle provided by the dealership as illegal payment to the player. In order to maintain the gross fiction that student athletes were amateurs, not professionals, the refusal to compensate players was justified solely by their status as amateur student athletes. This effectively meant that the student athletes, in their capacity as athletes were expected to perform a job, both in practice and during game time, for which the university was not compensating them, despite the fact that the football or basketball program is often the economic engine of the institution. In many American states, the highest paid public official is a college football coach. It is also no accident that the best football programs in the United States are found in the South East Conference, geographically located in b the part of the southern United States known most for its attempt to secede from the union over their continued desire to hold Black people as slaves.

One especially egregious case is the University of Mississippi, whose team is called the Ol’ Miss rebels, an obvious reference to the Confederacy. To make matters worse the short form, Ol’ Miss is not itself primarily the short form of Mississippi, as I thought for the longest time.. Instead ‘Ol’ Miss’ was how slaves were expected to refer to the wife of the plantation owner. Thus Black men, in order to further their prospective career as a professional football player are forced to don jerseys with explicit reference to the Confederacy, and fans cheer on the team with Chants of Ol’ Miss, which is also stamped on the sides o their helmet, reminding these young Black Men that the south still hates Black people and would still rather they were slaves. Then, when you realize that these young Black men are performing every weekend for paying fans, a significant amount of whom are white men, damaging their bodies and brains for the possibility that they might hit a payday large enough to help their families escape poverty stricken neighborhoods that glamorize gang lifestyles. A number of basketball players have talked about growing up in Compton, Los Angeles, a largely African American community that was a focal point, along with the broader area of South LA, during the Rodney King Riots in 1992. Players have talked about how being a professional athlete was his family’s ticket out of parts of LA that continued to heave trauma upon trauma on their families and comminuties.

To bring my observations back to the Fanon reading, it seems to me that the pursuit of professional athletic by Black men in the United States has the same effect on them as do the language observations made by Fanon, in a conceptual space Fanon thinks of as non-being These young Black men become completely integrated into the cultural pursuits of the wealthy white man, dependent upon his graciousness to play through college and get to the pros, where, once again, the wealthy white man becomes the primary consumer of their athletic labour. To quote Fanon once again, “The more the black Antillean assimilates the French language, the whiter he gets—i.e., the closer he comes to becoming a true human being,” would become in my proposed observation about professional athletics, The more the Black American man assimilated the cultural touchpoints of the white man, in this case, football and basketball, the whiter he gets, which is, for Fanon, a space a non-bing, the soul of teh Black man having been edxploited for the purpose of the colonizer.

It is only once the young Black man makes it to the professional leagues that he begins to be compensated for his athletic labour, until that point, his labour had been performed almost exclusively for the entertainment benefit of wealthy white men, without receiving any meaningul compensation for his labour. That is to say that, until the young Black man, proves to the wealthy white man that he is one of the best athletes in his sport, the young Black man is the wealthy white man’s athletic slave. Once again, the American south has become the focal point of a different kind of slavery. Instead of plantations, it is football stadiums and basketball gyms that serve as hosts o 21st century Black slaves in America. And yet, following Fanon, the more the young Black Man integrates himself into the athletic money machine, the more his Blackness becomes a commodity to be bought and sold for profit by the wealthy white man, and the more he loses touch with what makes him a Young Black Man, as he must make every effort to integrate himself into the good graces of the wealthy white man, who willceither draft him on draft day, or pass him over in the same way the wealthy white man passed over other young Black men t the slave markets of the 18th and 19th centuries.

This reality, alone should be all the reason that Colin Kaepernick needed to refuse to stand for the national anthem, saying, ““I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color. To me, this is bigger than football and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way. There are bodies in the street and people getting paid leave and getting away with murder”, referencing a series of African-American deaths caused by law enforcement that led to the Black Lives Matter movement and adding that he would continue to protest until he feels like “[the American flag] represents what it’s supposed to represent” an action that resulted in his exiting the league, cutting short his professional career/

Ta make matters worse, the slavery of young Black men occurs under the guise of education. White culture places significant value on a post secondary education, and so white men have convinced themselves that it is a-okay to exploit the labour of young Black men for profit because his generosity of free tuition is compensation enough. After-all, says the white man, via the NCAA rulebook, they should be grateful that they’re able to get a free education and that they’re not back on the plantation.

I am deeply indebted to my friend Fitsum Areguy, who was the first person to raise the status of young Black men in professional sports with me. While the ideas in this reflection are all mine, it was conversations with Fitsum that first helped me to think deeper about my consumption of professional sports, sports that rely on the exploited labour of young Black men to succeed/. I am not yet sure what kind of action, if any I should take, but I am grateful for the opportunity to think deeper about the connections between racism and sports. Fitsum is the leader of a very interesting community journalism project sponsored by Textile, a Waterloo Region Non-profit, that he co-founded, seeking out opportunities for community journalists whose voices may now go unheard. This project, Media Media, is raising funds that will go to three journalists from the Waterloo Region enabling them to tell the stories of their community in their own language, and with their community’s unique langauge use, a very fitting theme in light of the Frantz Fanon reading. I would invite anyone who wants to support a community project that will provide real pay for work being done by people of colour, including Black men, in the Waterloo Region. Fitsum has provided me with a short blurb about this project. If you are interested, please check it out further here.

Media Media is a community-driven journalism initiative that honours people’s linguistic and narrative sovereignty that have been harmed, silenced and oppressed by mainstream media. In this model, the people who are generally considered sources take the lead in telling their own stories rather than stories being told about them. In our region, there are many hidden initiatives that are exemplars of social infrastructure.

Three community-driven initiatives will be selected and mentored over the course of three months in weaving the narrative of their beginnings, their makings and their visionings. This initiative is expansive in the ways that it will allow for the storyteller to document, report on, and archive their presence. Language and medium have both been barriers and tools of control in media. Thus, we will not restrict the initiative to one media format; we will facilitate storytelling that is investigative, critical, and personal in a variety of ways (e.g., long-form, podcasts, photo essays, data visualization) and diverse formats (e.g. text, audio, video, and visual art)